Kevin Kruse on the history of populist backlashes

Kevin Kruse explains how Americans have pushed back against the rich throughout history.

Americans are not happy with billionaires having so much power and influence in our society these days. That's what the polls say, at least. A YouGov poll from earlier this month found that 80 percent of Americans believe income inequality is a "very big" or "somewhat big" problem. About 59 percent said the government should do something to address it.

Polls show that 61 percent of Americans believe billionaires aren't taxed enough. A Harris poll from November found 53 percent of Americans think billionaires are a threat to democracy. The polling also finds that the tech billionaires, specifically, are very unpopular.

So we've got a country full of people who are pissed off at the rich, essentially. I can't blame them. I'm also unhappy with the rich. In order to better understand what's going on here, I thought it'd be helpful to talk to a historian about times in American history when there have been populist backlashes.

We'll start at the beginning of the 20th century, when populism was really starting to take off in America. Kevin Kruse, a professor of history at Princeton University, tells me this was the first of several backlashes.

"Populism comes about as a counterpoint to the aristocracy," Kruse says. "It's very much class-driven through the first half of the 20th century... It's all about the working classes and farmers trying to create some sort of counterweight to the incredible power that industrialist capitalists—the kind of robber barons of the late 19th century—were exercising."

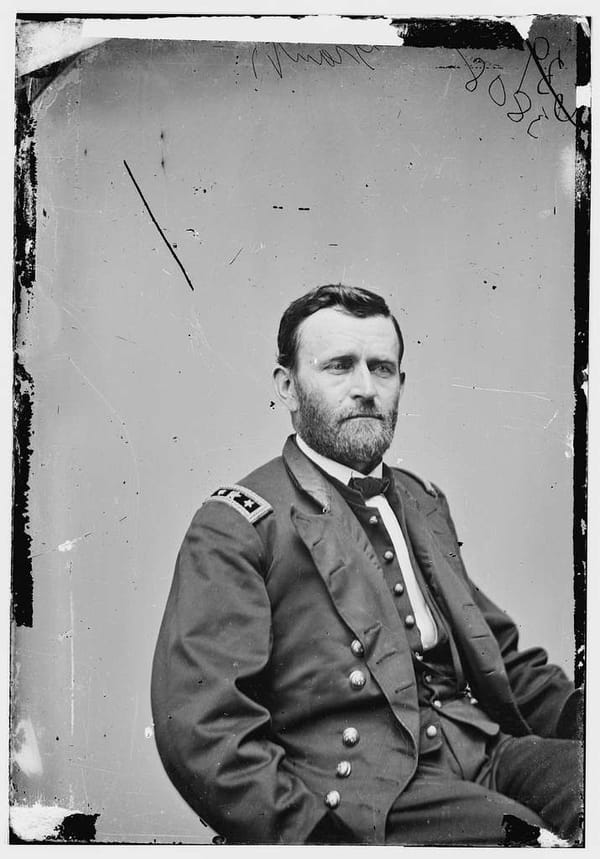

Kruse says that at the beginning of the 20th century, you'd look at figures like Huey Long and William Jennings Bryan as leaders of this movement. There was talk of "nationalizing wealth, giving everyone a fair share of money and breaking up the banks," he says. Obviously, the Great Depression further spurred people's concerns about wealth and power, and it made them want politicians to take more drastic steps to help the common man.

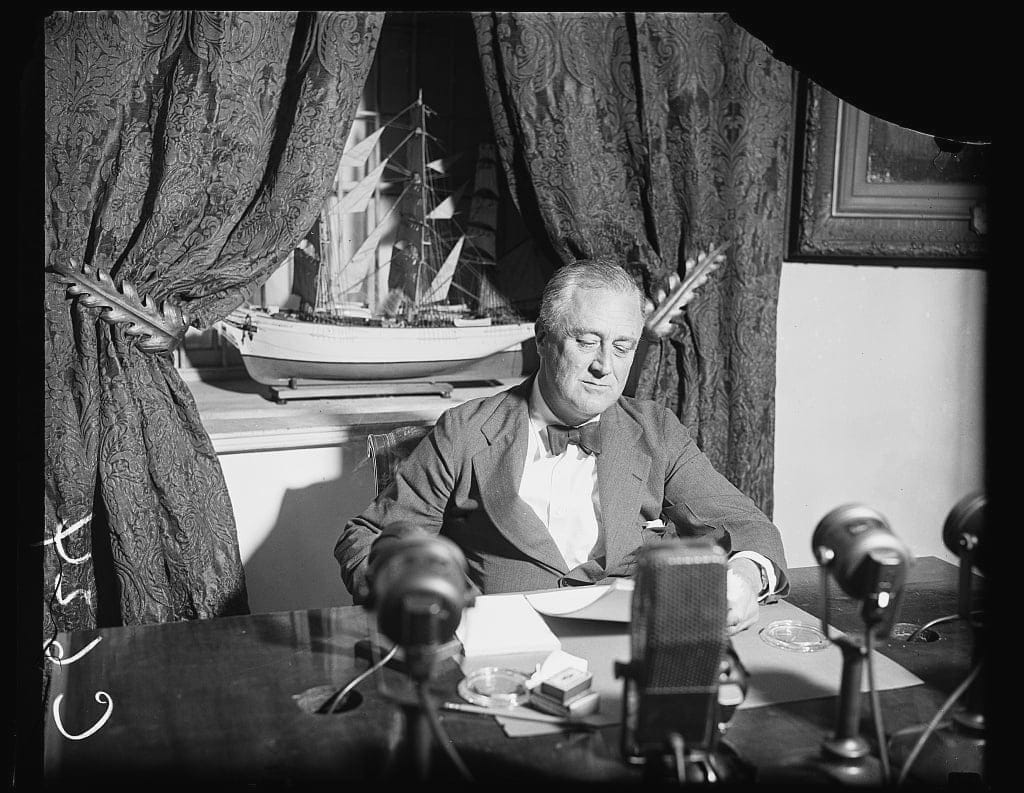

"FDR very much rides an existing wave of populism," Kruse says. "There’s a series of hearings held by the Senate Banking Committee… called Pecora hearings, and they bring very powerful men from these banks and single them out for investigations and condemnation."

These hearings pointed to the wealthy as the bad guys. By 1936, Kruse says, FDR was at Madison Square Garden, saying, "I welcome their hatred" about those rich and powerful individuals.

"He understands that this is good politics," Kruse says. "The underlying power of populism is that if you can single out a few bad people who are to blame for everything, you can get a lot of people to vote for that. The numbers are on your side."

Of course, Donald Trump has attempted to portray himself as a populist, even though he's not one, for the same purpose. He'll use some of the rhetoric of populist figures in his speeches and then go home and cash checks from fossil fuel and tech billionaires. Kruse says Trump is more like some of the populists that came after FDR.

"In the latter half of the 20th century, populism took a turn," Kruse says. "You can see this change in the career of George Wallace. He was originally a populist."

George Wallace, the former governor of Alabama, didn't find that populism based on class was working too well for him. He needed to change things up, and he found that a message focused on race and social issues was more effective.

"In the first version, it's oligarchs. Those are the bad guys," Kruse says. "In the second version, someone like Elon Musk or Donald Trump can pretend to be a populist, because the elites you're yelling at aren't corporate leaders or the very wealthy. The elites here are Hollywood, Harvard and things like that."

Trump has a list of "grievances" he often talks about, Kruse says, and they're all the same kind of culture war stuff that George Wallace pioneered. When Kruse plays George Wallace clips for his students, he says they instantly recognize the similarities.

Further along in the 20th century, we had a populist movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s. This was the hippie rebellion against the elites and consumerism. Kruse says that backlash was generally against the "establishment," which could mean Democrats, Republicans or anyone else with power. What they were fighting for was sometimes harder to define, besides obvious things like ending the Vietnam War.

At the end of the 20th century, there was something of a populist movement against globalization, as trade deals like NAFTA were being adopted in the early 1990s. Kruse says Trump definitely learned some things from this era.

"Trump really folded in that Pat Buchanan-style populism, which blended the George Wallace racism and nativism with a critique of foreign trade," Kruse says.

Now, well into the 21st century, we could be looking at the first real revolt against the rich in some time. There was the Occupy movement in the early 2010s, but that only captured a segment of the population. Today, there seems to be much broader agreement that enough is enough when it comes to how the rich are exerting their power.

"Once the people get their mind set on something, and the numbers are there, it's not up to the politicians to bend it to their will. They're going to find someone to represent them who speaks for them," Kruse says. "It's either going to be the people currently in power who agree, or they are going to find new people."

Essentially, Kruse thinks politicians who don't take notice of this shift in public opinion could find themselves in trouble. The people are saying they want elected officials who will push back against the power of the wealthy, and if a politician won't do that, the voters will find someone who will.

"I think that's something we're seeing now with the real effort to primary a lot of Democrats," Kruse says. "The base really wants people who are ready to stand up and fight."

Some Democrats have been railing against the oligarchs for years now, and it seems likely they'll continue to maintain or gain support. Those who keep taking money from the billionaires and try to avoid doing much of anything about their influence might end up facing substantial resistance.

The ultra-rich have corrupted our democracy and done significant harm to the fabric of our society. The people are upset about that and are looking for change. Any politician who wants to succeed should keep that in mind.