What the Red Scare can teach us today

Many of the things that happened during the Red Scare mirror what's happening today.

There have been two Red Scares over the course of American history, and it appears we may be witnessing a third. Whether they’re calling their perceived political enemies "antifa" or "communists," the Trump administration, its supporters in Congress and its allies in the media are on a vendetta to label large portions of the public as enemies of the state.

Increasingly, they’re calling their opponents "terrorists," as we’ve seen in countries like Russia and Turkey. Members of this administration, including the vice president, have called on people to contact the employers of people they disagree with so they'll be fired.

Most Americans think of the Red Scare and recall the actions of Sen. Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee throughout the late 1940s and early 1950s. To this day, we refer to an unreasonable campaign against one's political enemies as "McCarthyism." There are some notable differences between what happened during those years and what is happening right now, but there are also some clear and rather alarming similarities.

Clay Risen, an award-winning historian and a reporter for the New York Times, is the author of a book titled "Red Scare: Blacklists, McCarthyism, and the Making of Modern America" that was published earlier this year. He tells me that the Red Scare was, at first, based on reasonable suspicions.

"There's certainly a there there, right?" Risen says. "There's the general context of the Cold War, and I think, very legitimately, people had reasons to be concerned about what the Soviets were doing. There was evidence from the FBI... that Soviets had spied on the United States."

After all, it was discovered in 1949 that the Soviets had stolen nuclear secrets from the United States to build their first atomic bomb. This was obviously a massive scandal that greatly heightened fears surrounding what Soviet spies might be capable of. However, Risen says that Soviet espionage was almost nonexistent throughout the 1950s.

"The Soviets had essentially shut down their espionage efforts," Risen says. "In the face of all of this, it seems like an immense overreaction on the part of the government and on the part of American society to launch what essentially was a witch hunt—going after people who had no affiliation with any of these activities but were affiliated with a group that was affiliated with a group that had a connection to the Communist Party."

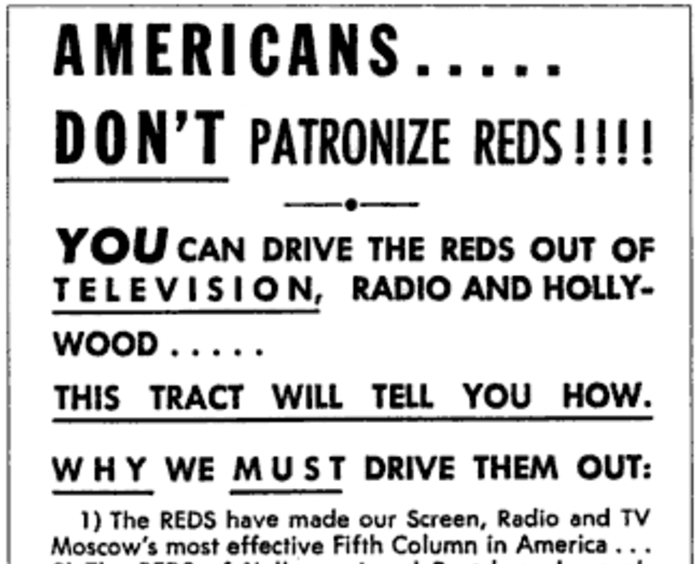

Efforts to hunt down communists infected every aspect of American life. Hollywood was famously targeted, and people in the film industry ended up on blacklists that effectively ended their careers, but the careers of people in many other industries were also destroyed.

"There were anonymous tip lines," Risen says. "If you thought that someone in your office was questionable, or if you just didn't like someone in your office, it didn't really matter, because it was anonymous. You could report them."

Mass surveillance was done on employees throughout the country to determine if any communists were lurking around. Anti-communist propaganda was common at the time and made many Americans extremely paranoid.

"Companies, particularly large companies, had designated security officers whose job it was to kind of run this operation, and they would be in touch with the FBI," Risen says.

A lot of what was happening was not the direct result of government action but rather a culture of fear that was festering at the time. People thought that they needed to participate in this hunt for communist infiltrators to avoid potential government persecution and to show their allegiance to the country.

"Oftentimes, censorship and repression that originates with the government doesn't actually have to be executed by the government, and just the implication of a threat is enough to get corporations and individual people really scared and give them a very strong incentive to do something on their own," Risen says.

You might call that complying in advance. Imagine corporations doing that today. How cowardly that would be.

One difference between the time of the Red Scare and today is the behavior of the president. During the Red Scare, Americans didn't see the president taking the lead on these efforts to root out communism. Presidents certainly spoke out against communism, but they didn't encourage the actions of people like Sen. McCarthy.

"We had presidents, both in Truman and Eisenhower, who were anti-communist but also very dedicated to the rule of law," Risen says. "They didn't really believe in the charges of the Red Scare, and ultimately they did the best they could to kind of tamp it down. Today we have the opposite."

Today, we see the president rabidly going after his political opponents and making wild accusations about how they're allegedly harming the country. We see him using ICE and the military to attack Americans in the streets of our cities. As Special Counsel for the U.S. Army Joseph Welch asked of Sen. McCarthy toward the end of the Red Scare, we must ask, "Have you no sense of decency, sir?"